- Dan Immergluck's Newsletter

- Posts

- Reflections on Some Surprising and Confusing Ad Hominem Attacks from a Major Public Figure (No, not that one)

Reflections on Some Surprising and Confusing Ad Hominem Attacks from a Major Public Figure (No, not that one)

On being personally and publicly attacked for questioning a major policy initiative of Atlanta Mayor Andre Dickens

It has been an interesting couple of weeks for me, to say the least. About two weeks ago, I found myself on the receiving end of an ad-hominem, personal attack on social media by a major public figure, Mayor Andre Dickens of Atlanta. Mayor Dickens was responding to what I think it is fair to call a fairly anodyne post on Linked-In of an October 14th article in the Atlanta Journal-Constitution, with some quotes pulled out in my original post. I thought I should take some time to reflect on this, and, especially, to thank those folks who have offered me support (sometimes understandably quietly) as this played out.

First, I think a very brief explanation of the policy proposal and tax increment financing, called tax allocation districts (TADs) in Georgia, is required here. The AJC article concerned a major proposal by the Mayor to extend all of the TADs in the City of Atlanta until 2055, which would have major, long-term structural implications for the city’s public finances and its ability to fund basic services, schools, and affordable housing throughout the city. The article included quotes from critics of the proposal, including myself and one other person, but also substantial quotes from the mayor’s chief policy advisor arguing for the blanket TAD extension.

These TADs are all at least 20 years old, and some are over 30 years old. The state enabling legislation, and good tax increment finance policy generally, was designed with the notion that TADs should target “distressed” areas and enable the concentration of public investment in order to “jump start” development and real estate markets in these neighborhoods. TADs work by freezing current property tax revenue going to general city revenues, county revenues, and schools at their current levels and then direct any growth in property taxes after TAD designation toward development activities within the TAD, including the repayment of bonds used to finance projects. All TAD dollars must go for activities taking place solely in the TAD. TADs are generally expected to meet the “but for” criterion of good economic development subsidy practice. That is, but for the TAD designation, the growth of property values (known as the “increment”) that is now directed to the TAD alone, would not occur. To the extent that this is not true, some or all of the growth in property tax revenue would have occurred without the TAD designation, and therefore the TAD merely redirects tax revenues that would have occurred anyway away from schools and general revenue budgets toward subsidizing projects in the TAD. Therefore, the use of TADs makes more sense in places where property values are declining or stagnant than it does where values are already increasing or likely to increase without the TAD. In gentrifying areas or neighborhoods that are experiencing healthy property value growth, TADs are less likely to make a difference in the trajectory of property values and so are likely to merely “capture” revenue that would have occurred anyway, for the purposes of subsidizing development.

The TADs in the city were all designated before 2006, and some of them much earlier. The critical context here is that, especially since the end of the foreclosure crisis in 2011, the City of Atlanta has been one of the fastest gentrifying cities in the country. Since 2012, property values have increased dramatically across the city and especially in the most valuable, largest TAD, the Beltline TAD, which is now generating well over $100 million per year in increment that, in 2030, is supposed to return to the schools and the city and county general revenue budgets. Much of the property wealth in the Beltline TAD, and many parts of other TADs, will continue to grow without their terms being extended. In these areas, the TADs have done their jobs, and it is time to return the now robust property tax revenue to their intended sources, including public schools, which are supposed to receive 50% of the property tax base but are experiencing fiscal pressures, partly due to the extensive use of TADs in prime real estate areas.

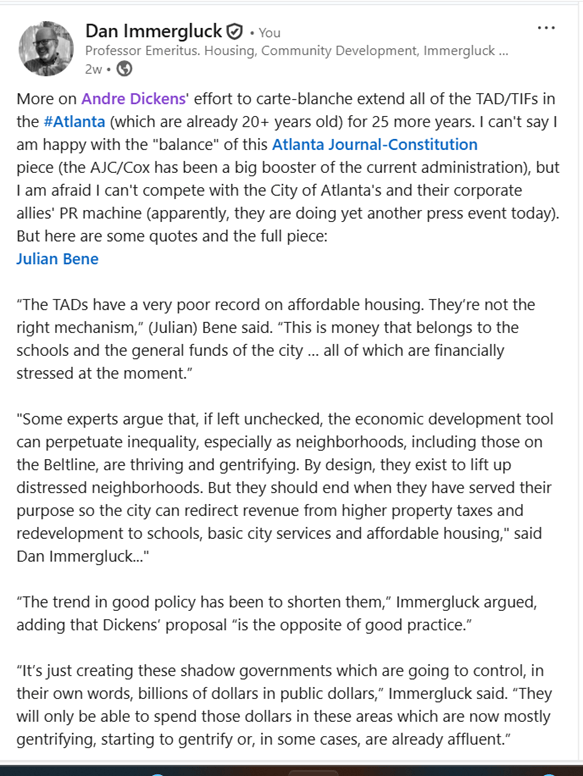

All of this is to say that I publicly criticized the across-the-board TAD extension in the October 14th AJC article and posted the article on Linked-In.

The Mayor personally (as he clarified after his initial response) responded the same day by attacking me personally. Here is his reply:

Well, after all these personal attacks, I felt compelled to respond; it was the Mayor of Atlanta after all. And so I did:

The Mayor’s vitriol and the spurious nature of the comments were a significant shock to me. It is not that I am naïve about the anger that politicians can sometimes exhibit. During more than thirty years of advocating for and against policies at the local, state, and federal levels, I have certainly seen politicians get angry. For example, I recall being at a meeting with the long-time head of Chicago city council, Ed Burke, around 2000, when I was working as an advocate to urge the city to adopt an anti-predatory lending ordinance. Alderman Burke had relationships of some sort with the banking giant Citigroup, which at the time owned a notorious subprime mortgage lender. The company did not like an ordinance we were supporting because it would classify much of the lending of this subprime lender as predatory, and so Alderman Burke was not happy about the bill. He pounded loudly on the table right in front of me accusing me and others of besmirching the reputation of Citigroup and its leadership. However, the alderman did not insult me personally, did not make ad hominem attacks, and expressed his anger in a meeting, not in a broad public space, yet alone on a major social media platform (which did not exist at the time of course).

But I was also shocked at the comments the Mayor made in part because he had seemed to value my policy expertise, at least occasionally, over the previous 10+ years. Starting as early as 2014, when he joined city council, he reached out to me to meet and get my input on city housing policy. We corresponded repeatedly during his time on council. He even spoke to my classes a couple of times. And then, after his mayoral election, he invited me to serve on his 2022 Transition Committee, which I agreed to do with the stipulation that I would not hesitate to speak out if I disagreed with his administration’s policies.

I think it’s no big secret that I have been critical of recent Atlanta mayors regarding their affordable housing, public finance, and urban development policies. In fact, much of my most recent book focused on major policy mistakes in the context of a gentrifying Atlanta since the 1996 Olympics. However, I wrote a recent piece that, while questioning some of the national hype that the Dickens Administration has received regarding its affordable housing policies and pointing to a continuing lack of deeply affordable production, acknowledged that Mayor had significantly increased its overall affordable housing numbers compared to his immediate predecessor.

Beyond my direct responses to his Linked-In comments, I decided my focus should remain on the substantive problems with the TAD extensions. I wrote an op-ed for the AJC outlining my arguments as to why the blanket TAD extensions were bad policy, not bringing up his ad-hominem attacks.

In the aftermath of this fracas, I have received a great deal of support, on social media and via private messages and emails, from colleagues, former students, and even some complete strangers. This has been heartening and very much appreciated. Many were horrified by the way the Mayor behaved on a public forum. Others were simply glad that I had articulated why the TAD extensions were poor policy even after the Mayor’s public, personal attack.

However, I did receive an email from one person who argued that, now that I no longer live in Atlanta, I should not comment on policies in the city or region. For an urban planning scholar, this seems an odd suggestion. My commitment as a scholar is to help cities and regions become more just, equitable, and sustainable places through my expertise, research, and teaching. My work might have me address policy and planning in Atlanta, Chicago, Barcelona, or Beirut, as long as I develop sufficient knowledge and experience to do so. Just as political scientists might be concerned with free and fair elections anywhere in the world, my concerns for affordable housing and equitable urban development are not constrained only to the place where I am currently living.

At the same time, I will push back against the author of this email even more. My continuing concern about Atlanta, and especially about the lives of lower-income Atlantans, goes beyond my broader scholarly concerns. I taught and did research in and about Atlanta for 20 years. I worked for better housing and urban development policy in the city and across metropolitan Atlanta for the same length of time. About half of my scholarship over the last twenty years of my career, and the majority of the policy work I engaged in, has concerned Atlanta. I taught well over 750 students in the city, many of whom are now practitioners and policymakers in affordable housing and urban development in the region. I remain in contact with many of them.

Even though I moved to Chicago recently for personal reasons, I have kept abreast of policy and urban development in Atlanta partly because I remain deeply concerned about the region. I will always remain connected to Atlanta.